By Tshiamo Tabane (Candidate Attorney),

Michelle Venter (Senior Associate),

and Chantelle Gladwin-Wood (Partner)

16 September 2025

Short-Term Rentals: Why They Belong in the Residential Property Rates Category

INTRODUCTION

South Africa’s residential rental market has undergone a significant transformation. The growing demand for alternative accommodation, combined with the digitalisation of property platforms, such as Airbnb and Booking.com, has resulted in properties being increasingly let for short-term purposes. According to the PayProp Rental Index1, the first quarter of 2025 saw the strongest quarterly growth in years, reflecting the ongoing growth in property rental activities.

One major area of concern, however, is the categorisation of short-term rentals under Municipal Property Rates Policies. This article examines the legal framework governing this issue, with specific focus on the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality, and explains why the categorisation of such properties as “business and commercial” is problematic and arguably unlawful under current legislation.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004 (“the MPRA” and/or “the Act”) empowers municipalities to levy rates on properties and mandates the adoption of a Rates Policy by a municipality. Section 3 of the MPRA requires municipalities to ensure that their policies are consistent with the objectives of the Act, as well as the constitutional principles of equity, fairness and administrative justice2.

Of particular relevance is section 8(1), which provides that municipalities must determine property categories based on one or more of the following criteria:

a. The use of the property;

b. And/or

c. The permitted use of the property (i.e. zoning).

This framework makes it clear that categorisation must be guided by the actual and lawfully permitted use of the property, which many municipalities appear to overlook in practice in order to earn additional rates revenue. In its most recent policy, effective 01 July 2024, the City of Johannesburg defines “Residential Property” as:

“Property used exclusively for human habitation primarily used for or permitted to be used for residential purposes; and excludes, amongst others, guesthouses, bed and breakfast establishments, [and] premises for human habitation for which the main or primary purpose is short-term rentals.”3

This definition is particularly contentious because it excludes short-term rentals from the residential category, even where the property is zoned residential and still used for human habitation. Instead, such properties are often categorised as “Business and Commercial”, which is defined as:

“Property used for the object of the acquisition of gain or profit by a natural or juristic person and the revenue which is derived thereby goes to the proprietary members as the proprietors of the concern.”4

Understanding the City of Johannesburg Land Use Scheme 2018 (“LUS”) and Short-Term Rentals

The City of Johannesburg’s Land Use Scheme (2018) categorises land uses based on zoning and specific permissions:

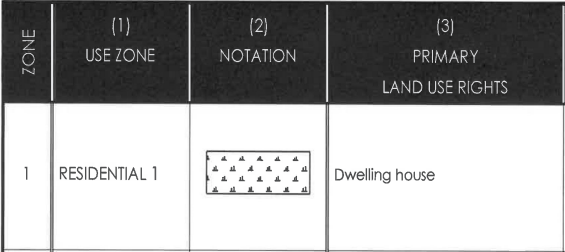

- Primary Land Use Rights: These are the default uses allowed under a property’s zoning. According to the LUS, properties zoned as “residential” automatically allow the owner to use the property as a dwelling house/unit. This is referred to as a “primary right”. For example, a property zoned as “Residential 1” typically permits a dwelling house as the primary use. See below:

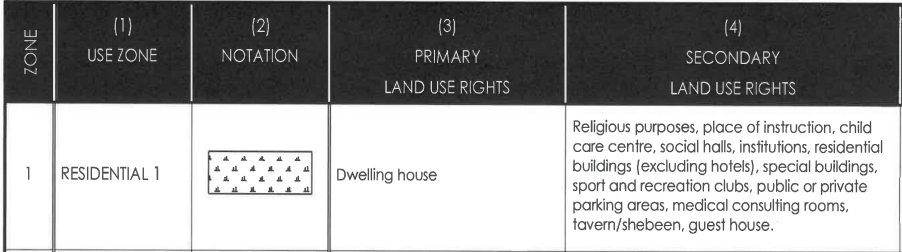

- Consent Uses: These are additional uses that may be permitted on a property, provided the owner applies for and receives formal approval from the City. For instance, operating a guesthouse falls under “Secondary Land Use Rights” and would require consent use, even on a property zoned as “Residential 1″. See below:

It’s important to note that the mere act of renting out a property on a short-term basis, such as through platforms like Airbnb, does not automatically transform the property into a guesthouse or bed and breakfast.

A “bed and breakfast” under the LUS is defined as:

“a building/s in which the resident manager provides lodging and meals for compensation to transient guests who have permanent residence elsewhere provided that:

- (The number of rooms /suites may not exceed ten (10) without the written consent of the Council in addition to the accommodation of the resident manager

- The buildings may include self- catered suites

- No buildings may be converted into dwelling units or be sectionalized.”

A guesthouse is defined in the LUS as:

“a converted dwelling house or dwelling unit whereby the resident household / person lets out individual rooms for temporary residential accommodation, with or without meals, with the proviso that all amenities and the provision of meals and beverages shall be for the sole benefit of bona fide guests and the resident household /person. The premises shall not be used for functions such as conferences, promotions and /or receptions.”

ANALYSIS

Should a Property Advertised on Airbnb be Automatically Considered as a BnB?

Despite the name “Airbnb,” a property listed on the platform should not automatically be considered a bed and breakfast under the COJ’s LUS. Legally, to qualify as a bed and breakfast, certain requirements must be met: it must have a resident manager on site, provide lodging and meals for transient guests, and cannot have more than ten rooms without council approval.

Airbnbs do not automatically meet these requirements, such as, for example, in the case of entire-home rentals with no resident manager.

Should It Be Considered a Guesthouse?

A property qualifies as a guesthouse under the LUS when the resident household (meaning the person who lives in the house – be it the owner or a tenant of the owner) rents out individual rooms for temporary accommodation, with or without meals, and without hosting events like conferences or receptions. In many cases, an Airbnb where the owner lives on-site and rents rooms could qualify under this definition. However, if the property is rented out as a full home with no live-in resident, it would not be a guesthouse and would instead remain short-term residential use, under the property’s primary residential rights.

What This Means for Property Owners Renting Out Their Properties Short-Term

As long as the property is primarily used as a residence, it remains within the scope of its primary rights. The City of Johannesburg’s Land Use Scheme recognizes that guesthouses and bed and breakfasts, as well as short-term rentals, can fall within residential use categories, provided they are operated in accordance with the scheme’s provisions and any necessary consents are obtained.

Accordingly, by excluding these properties from the “Residential” rates category in its 2024/25 Property Rates Policy, the City creates a direct inconsistency between its own land use planning framework and its Rates Policy, which is difficult to justify (if not patently unlawful) in light of the MPRA’s requirement that property categories be determined according to actual and permitted land use. This blanket classification (of all guest houses, BnB’s and short term rentals as “business and commercial” properties for rating purposes) does not consider whether the property is operating within its primary rights or has obtained the necessary consent use and may result in legal challenge. Such an approach may lead to inconsistencies and potential legal challenges, as it overlooks the nuances of zoning laws and the specific permissions granted to property owners.

What Should the Categorisation Be?

Even where a property is used for short-term letting, its categorisation for rates purposes should remain as “residential” if the zoning is residential alternatively if residential use falls within the property’s primary rights, and where the use is for residential purposes. Where the whole house or unit is let out, there is no argument to be made by the City that the unit/house ought to be categorised as a BnB, or Guesthouse, or that it ought to be in the “business and commercial” rating category. Simply put, it ought to be in the “residential” rating category.

Where a person resides at the property and rents out the rooms one by one, the property might fall under the definition of a “BnB” for the purposes of the zoning laws, but this does not make it “business and commercial” for the purposes of the rating laws. Where the zoning (land use rights) and use remain residential, then the property should be categorised as “residential” for property rates purposes too. This is what is prescribed – and must be done – in terms of the MPRA.

Section 8(1) of the MPRA requires municipalities to consider the use, permitted use, when determining property categories, in line with existing zoning and planning frameworks. A municipality that disregards this regulatory framework (such as in the case referred to above herein where the COJ has attempted to define properties that by law, in terms of the MPRA, must be residential, as “business and commercial” purely in order to obtain more rates revenue) undermines the municipality’s own planning instruments and exposes its to judicial review, for acting ultra vires (outside the scope of its authority). It also further erodes the trust of the public, which is the case of the COJ is already in short supply.

COMPARING LONG AND SHORT TERM RENTALS

Firstly, there is no universal definition of what short term rentals even are. Some people describe them as rentals for shorter than 3 months; others define them as rentals shorter than one month (because a month to month lease is generally not considered a short term rental). Even if there were a universally accepted definition, the mere fact that the rental period is shorter than in a traditional longer term lease, does not provide a municipality with any justification for treating the property differently to a residential “long term lease” for rating purposes.

Nor does the fact that the owner might be generating income from the rental change the situation. In long term rentals, owners generate income, but again this doesn’t give the municipality the right to change the category for rating purposes from “residential” to “business and commercial”. So long as the zoning and use remain residential, there can be no argument from the municipality’s side because in the event of a contradiction between the MPRA and the provisions of the City’s rates policy, the MPRA will come out on top every time. This means that any provision of the City’s rates policies that are contrary to the MPRA are invalid in law and liable to be set aside by a court.

UNFAIR DISCRIMINATION AND ARBITRARY, CAPRICIOUS AND UNLAWFUL CATEGORISATION

Short-term rentals, by their very nature, involve the occupation of a dwelling unit for temporary residential purposes. Short-term tenants live, sleep, cook, and dwell in the unit as they would in any medium-term or long-term residential rental property. Both short- and long-term rentals involve residential occupation for human habitation, and both generate income – yet only the short-term variety is penalised by being placed in the more expensive “business and commercial” rates category. This unequal treatment is arbitrary, and lacks any rational basis as to why these property owners should be charged higher rates than their counterparts in the case of “normal” long term rental properties. Such a blanket classification not only violates the MPRA but also disrupts the coherence between a municipality’s Rates Policy, zoning scheme, and planning regulations.

There can be no doubt that this discrimination against short term rental properties has been brought about by the municipality purely in order to obtain higher rates revenue – rendering this arbitrary discrimination capricious and unlawful.

CONCLUSION

The City of Johannesburg’s current treatment of short-term rentals reflects in its rates policy a disconnect between land-use Regulations and the City’s Property Rates Policy. This approach not only imposes an undue and discriminatory financial burden on property owners who use their residentially zoned properties for short term rentals, but also raises legal concerns under administrative and constitutional law that the provisions of the City’s rates policy in this regard are unlawful for being ultra vires the MPRA.

Unless municipalities harmonise their Rates Policies with zoning schemes and the provisions of the MPRA, such property categorisations will remain vulnerable to legal challenge. Short-term rentals, so long as they operate within the bounds of residential zoning, should be categorised as “residential” for property rates purposes.

The proper application of the MPRA requires that short-term rentals be categorised as “residential”, unless there is a demonstrable change in zoning or an approved deviation. The recategorisation of these properties as “business and commercial”, simply because they generate an income, is legally flawed and results in arbitrary treatment, undermines planning laws, and exposes municipalities to legal challenge.

Please note: Each matter must be dealt with on a case-by-case basis, and you should consult an attorney before taking any legal action.

1PayProp South Africa (2025), “Will strong rental growth continue in 2025?” accessed at https://www.payprop.com/za/blog/will-strong-rental-growth-continue-in-2025

2Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004: sec 2

3City of Johannesburg Property Rates Policy 2024/2025 at para 3.2.1 and 3.2.3.1.

4Note 3 at para 3.4.1.